The Feudal Age and the Samurai

At the onset of the feudal age, the Samurai were peasant-farmers who fought for their lords as well as they could when the occasion arose. This was similar to the peasant-farmer armies that could be raised in feudal Europe. As conflict became more frequent, it became necessary to train armed groups to protect the respective boundaries.

At this time, these armed groups were called Samurai or Bushi. However, their status in society was not established until the Minamoto family formed a military government in 1192. This military government (the Shogunate) strongly encouraged austerity and the pursuit of martial arts and related disciplines for the Samurai class. These studies were eventually rigorously codified and called Bushido —Way of the Samurai.

Development of Unarmed Techniques and Aiki-jujitsu [Top]

Varying battlefield situations and the technical requirements of feudal warfare led to the establishment of various Styles or ryu of unarmed combat, which were controlled by, and passed down through the large powerful families. One of these systems was Aiki-jujitsu.

During the 16th century, Japan was embroiled in civil wars.

Each feudal lord (Daimyo) struggled to maintain a powerful, independent position within the country. In order to do so, each Daimyo had to create a stable, unified force of his own, which required a very strong bond between the Lord and his Bushi (warriors).

Bushido, the code of the Samurai, was used not only to encourage the development of combat techniques; but also to cultivate qualities of justice, benevolence, politeness and honor; and probably above all to inculcate the idea of supreme loyalty to one's lord and clan.

It was during this period of almost constant regional warfare, local independence and feudal isolation that the refinement of unarmed combat forms flourished and thereby developed into very numerous and distinctive ryu or styles.

Aiki-jujitsu and Its Social Background [Top]

The Tokugawa period in contrast was relatively peaceful for Japan. Though the Samurai, as a class saw little combat, they continued to practice and refine the various martial arts of kenjutsu, iaijutsu bajutsu and jujitsu.

As the martial arts (and all of Japanese culture) became strongly influenced by Buddhist concepts, the fighting arts were transformed from combat techniques (Bugei) into "ways" (Budo), inculcating self-discipline, self-perfection, and philosophy. As a result, the dimensions of the martial arts expanded beyond the simple objective of killing an enemy to include the aspects of everyday living.

After the decline of the Samurai class, martial "techniques" became martial "ways"and a great emphasis was placed upon the study of Budo as a means of generating the moral strength necessary to build a strong and vital society. The Bushi, as a class, virtually disappeared under a new constitution that proclaimed all classes equal, but the essence of Bushido, cultivated for many centuries, continued to play an important part in the daily lives of the Japanese. This remains true today.

Budo, being less combative and more concerned with spiritual discipline by which one elevates oneself mentally and physically, were more attractive to the common people and were readily taken up by all classes, and people of every social strata. Accordingly, kenjutsu became kendo, iaijutsu became iaido, jojutsu became jodo and jujutsu became judo.

As a young man, Morihei Ueshiba (1968-1882), had an unusual interest in the martial arts, philosophy, and religion.

The environment of his youth, one of religious discipline and tradition, had an enormous effect on the course of his life.

In the year 1898, Ueshiba left his home village of Tanabe outside Osaka and traveled to Tokyo, seeking instruction in the martial arts. He actively investigated dozens of arts, but was eventually drawn to specialize in three: the sword style known as Yagyu Shin-Kage-ryu, the staff style known as Hozoin-ryu, and Tenjin Shinyo jujutsu.

In 1905 Ueshiba met Sokaku Takeda, head of the Takeda family, and began his study of Daito Ryu Aiki-jujitsu. In addition, he continued to practice the other arts he had learned in Tokyo, particularly kenjutsu and jojutsu. After four years of intense training Ueshiba was granted his masters licence in Aiki-Jujitsu and in 1925 Ueshiba organized his own style of Aiki-jujitsu, largely for his own spiritual and physical development.

To contribute to the evolution of martial "arts" to "ways" — Bugei to Budo — Ueshiba diligently applied himself to the reworking of the killing techniques he had been taught, and synthesized them into a form that taught harmony and reconciliation rather than violence and death. Ueshiba proclaimed that the true Budo (the way of the warrior) was the way of the peaceful reconciliation. He dedicated himself to the design of an art that would teach technical prowess and strength, and commitment to the self-discipline needed for personal growth. He dubbed this new "modern martial art" Aikido — which means "The Way Of Harmony".

Ueshiba continued to instruct until his death in 1968, earning the respect and admiration of all who met him. Before his death he received a government award as the designer of modern Aikido, and general acclaim for his effort to bring peace and enlightenment to all.

Gozo Shioda & Yoshinkan Style of Aikido [Top]

Ueshiba's most outstanding student was Gozo Shioda (1915-1994). It was this man who contributed much to bring about the increased popularity that Aikido has enjoyed since the war. This was especially so in the immediate post was years when the son of O-Sensei ceased any Aikido activities for several years and later came to train with Shioda Sensei and Saito Sensei.

Shioda entered Ueshiba's dojo at the age of 18, and lived and practiced there for eight years. Because he stayed at the dojo longer than any other student, and at a time of Ueshiba's greatest health and vigor, Shioda learned to sense the ways of the Master's mind and spirit.

In recognition of Shioda's progress, Ueshiba was to award him 9th Dan, the highest rank given by Ueshiba to any of his student's, plus his "Master" instructor's license.

Gozo Shioda Sensei's style of Aikido is known as Yoshinkan, a name that he inherited from his father who owned a Kendo and Judo dojo by that name. Yo means cultivating; Shin means spirit of mind; and Kan means house; thus Yoshinkan is the house for the cultivation of spirit and mind.

During the mid and late 1950's, having established the post-war position of Aikido in Japan, Gozo Shioda Sensei assisted Kissamaru Ueshiba in re-establishing the Aikido program at Ueshiba's dojo in Tokyo. From the early 1960's onwards Gozo Shioda Sensei then principally applied himself to developing the teaching program and uchideshi system at his Yoshinkan School and at dojos (primarily police and company schools in Japan). During this time the Aikikai Honbu dojo of Kissamaru was active in fostering the growth of Aikido overseas.

Gozo Shioda Sensei was respected the world over for his attitude toward the Budo disciplines and for his belief in Wa (Harmony) as a way of life. He remained involved in the teaching activities at the Yoshinkan Honbu until the time of his death.

In 1990 Gozo Shioda Sensei implemented the International Yoshinkan Aikido Federation (IYAF, renamed Aikido Yoshinkan Foundation in 2008) (Aiki News 1990 #85), the International Instructors Course, the Aikido Yoshinkan International quarterly magazine, and the provision of instructional videotapes (Quest) and book (Aiki News). Through these initiatives Gozo Shioda Sensei hoped to help more directly to cultivate the worldwide development and understanding in Aikido.

On creating the IYAF Shioda Sensei's official title became "Soke", which translates as founder and father. Soke Shioda passed away on July 17, 1994. His legacy lives on through the Shioda International Aikido Federation and Yoshinkan Aikido throughout the world.

Fred Haynes Shihan (8th Dan) [Top]

Having started in Tomiki Aikido in the UK in 1969, Fred transitioned to the Yoshinkan style in 1980 under Sensei’s Takeshi Kimeda, Mitsugoru Karasawa and Takashi Kushida (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) when he moved to Toronto. At Kimeda's dojo on Queen and Jarvis, Fred trained alongside Alister Thomson and Robert Mustard in the journey from 1st kyu to 3rd Dan gradings with Kushida Sensei and then onto the mats together at the Yoshinkan Honbu in Tokyo.

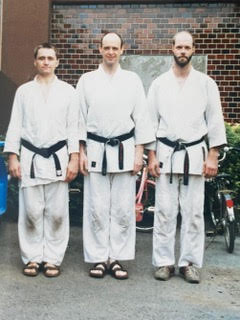

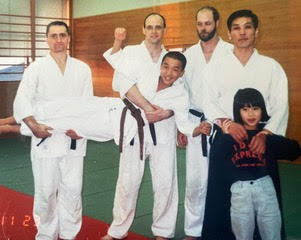

In the mid-1980s, inspired by the teaching of Shioda Gozo, Yoshinkan Aikido's founder Alister, Robert and Fred were accepted to train at the Yoshinkan Honbu (then in Musashi Koganei). Alister and Robert arrived in mid-1985, with Fred following in April 1986.

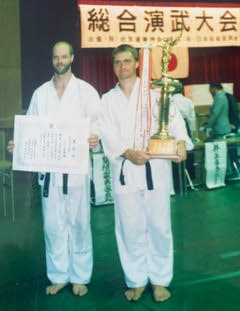

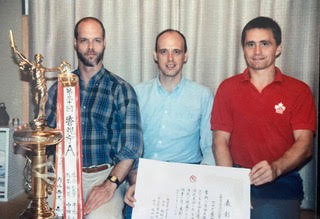

At the Honbu they completed the full-time professional instructor's course taught to Honbu instructors and the Tokyo Riot Police. In October 1988, with their embu training mentored by Takeno Sensei, Alister, Robert, and Fred achieved first place at the All Japan Yoshinkan Demonstration, a historic international first. In addition to Shioda Gozo, the instructors in Japan at the time included Takafumi Takeno, Tsutomu Chida, Tsuneo Ando, Kyoichi Inoue, Yasuhisa Shioda (3rd son of Gozo Shioda), Hitoshi Nakano, Kiyoyuki Terada and others.

Fred studied for eight years as a student of Shioda Gozo. From 1990 onwards, together with uchi-deshi Mark Baker, he worked closely with Shioda Gozo and senior Honbu dojo instructors in establishing the International Yoshinkan Aikido Federation (IYAF). In this role, Fred travelled extensively from 1990-2014, visiting dojos in Australia, Brazil, France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the UK and across Canada and the USA. On these visits and tours, he often accompanied Shioda Gozo, Kiyoyuki Terada, Tsutomu Chida, Kyoichi Inoue, Yasuhisa Shioda, Tsuneo Ando, Amos Lee Parker, Masazumi Matsuo, Chizuko Matsuo, Mark Baker, Jaques Payet, David Rubens, Joe Thambu, Gadi Shorr, Ikuo Watanabe and other Japanese and Western instructors. Renamed the Aikido Yoshinkan Foundation in 2008, the IYAF has been instrumental in fostering the explosion of overseas growth in Yoshinkan Aikido.

In 1990, Alister and Fred, together with Jim Stewart and Gordon Blanking, co-founded the Seidokan IYAF Dojo in Georgetown, Ontario. Fred taught at this "home dojo" for 14 years before moving to Vancouver Island in 2003. Here, together with Wendy Seward and Jim Kightley and supported by the Seidokan group, Fred co-founded Island Aikido. This relocated the Shinbukan IYAF Dojo founded by Jim and Wendy in 1990 in Waterloo, ON.

In early 2007, the Yoshinkan Honbu, with Dojocho Kyoichi Inoue, presented Fred's 7th Dan and IYAF Shihan designation. In 2014, Fred was presented with his 8th Dan by Shioda Yasuhiza. He was also awarded the red and white Kohaku Obi. In this special honorary belt, the white symbolizes the purity of spirit encouraged in Aikido practitioners, and the red signifies the intense desire and commitment to training and the sacrifices made to do so, a sense of “training until you bleed.” Fred believes the Kohaku Obi represents the Shioda family's regard for the efforts of all Aikido practitioners.

Article about Fred's 8th Dan award in Saanich News

Following an interrupted schedule in 2018-2022 to serve as Mayor of the Municipality of Saanich, Fred has returned to regular training at Island Aikido and is enjoying reconnecting and travelling to visit with old and new Aikido friends.